Housing targets that work

A dynamic, demand-driven model that ensures homes are built where people want to live.

The great majority of Victoria’s new housing should be built in high-amenity and infrastructure-rich areas. These are the places where the demand for density is highest, and where that density can best be supported.

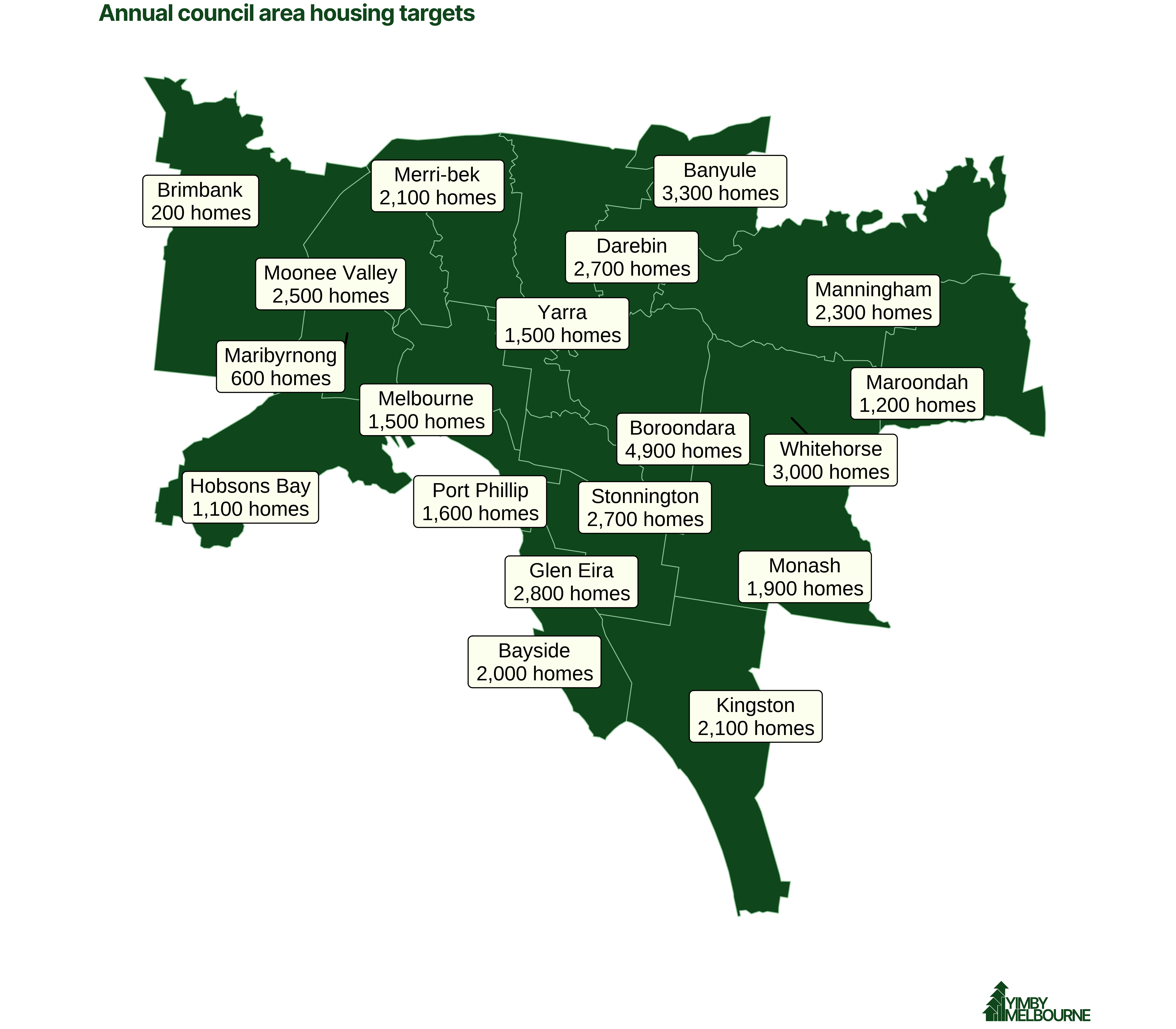

As such, we have allocated half of Victoria’s annual target of 80,000 new dwellings to 19 amenity- and infrastructure-rich inner-city Melbourne LGAs.

The selected LGAs are where our modelling indicates that demand for denser living is high, and where supply by the private market will therefore be most viable. Our modelling allocates a total of 40,000 homes per year across these LGAs based on development viability.

Targets are highest in places like Boroondara where density is low due high numbers of single-family homes on large lots near public transport, where there is strong demand for apartments.

Targets are lower in areas such as Maribyrnong, where apartments sell for much less and missing middle housing is therefore harder to build.

There are also some areas like Port Phillip, where demand for missing middle housing is high and yet there simply isn’t enough suitable land to build missing middle housing.

More housing could potentially be provided in these LGAs through rezoning of well-located industrial and commercial land. However, for the purposes of this report, we are only considering land on which housing is currently permitted.

Why Melbourne needs targets

Melbourne needs housing targets because it needs more housing.

With the exception of the City of Melbourne, inner- and middle-ring councils are currently not doing enough to house Melbourne’s future population. This has contributed to the city’s high reliance on greenfield development, which has seen more and more Melburnians pushed out toward our urban fringe.

The land use patterns that our city needs—dense housing in high-amenity areas, within highly walkable neighbourhoods—are largely absent. That is because, broadly, it is banned from being built. The best way to increase density across our city is to legalise density across our city.

Calculating targets

For a housing target to be meaningful, you need two key things. First, you need strong demand for more housing. And second, you need land available for development.

It is common practice for planners to calculate “zoned capacity”, which is the theoretical number of homes that could be built across an LGA if every lot were developed to maximum permitted density. We outline the problems with a reliance on limited zoned capacity later in this report.

To account for these problems, our model takes into account a number of factors beyond zoned capacity, including the demand, prices, and development costs across each LGA. The methodology can be found here.

Our model does not expect development to occur on every viable site. But councils with more viable sites are allocated a higher share of our total inner-Melbourne housing target of 40,000.

Updating targets

Housing targets should be updated by the state government every year, and if apartment prices fall in some areas, then the housing target will automatically fall as it will become clear that development is no longer profitable in that area.

The best way for a LGA to reduce its target is to make housing cheaper. And the best way to make housing cheaper is to make it abundant.

This system of enforced housing targets is designed to create a virtuous cycle that drives down prices across the entire city, creating a more affordable and equitable Melbourne for all.

Enforcing targets

There is currently no mechanism to ensure that councils actually permit the housing for which they claim to have zoned capacity. The Victorian Government should follow the advice of Infrastructure Victoria and the Productivity Commission to enforce housing targets through a set of robust carrot and stick incentives.

To deliver a high number of well-located homes across Melbourne requires more than just non-binding capacity targets that look good on paper. Rather, we need binding material construction targets that look good in real life. People do not live inside housing capacity; they live inside houses. And Councils must be kept accountable to that fact.

Targets should be reported on through a combination of development and building approvals, commencements and completions, and LGA progress should be tracked publicly against their annual targets.

Carrots

LGAs who meet or exceed their housing targets should be given financial rewards by the State Government. These rewards should come from the State Government’s consolidated revenue, and should be supplemented through distribution of the Commonwealth’s New Home Bonus.

In the YIMBY Melbourne’s 2023 report, Melbourne’s Missing Middle (pg. 41) we laid out a Residential Windfall Gains Tax that could be used to generate revenue in order to pay for these rewards. The WGT should be levied upon the first sale of any upzoned residential property after upzoning has taken place. In the Missing Middle Report, we estimated a conservative 4% uplift on all upzoned homes.

Our model proposes the upzoning of 781,956 properties total, with the WGT to be applied at first sale, regardless of the timing of the transfer. With the median value of houses in the area covered by this report at $1.19m, we estimate a revenue of $11.2 billion billion over the lifespan of Plan Melbourne 2050.

A minimum of 70% of WGT revenue should be hypothecated to Homes Victoria for the construction and maintenance of social housing. A portion of remaining revenue should be used to reward councils who exceed their housing targets, paid out annually and used by those councils to improve infrastructure and services for the people who live there.

It is worth noting that the Windfall Gains Tax is first and foremost a method of maintaining revenue neutrality. Regardless of the Government’s desire or ability to implement to implement such a tax, the immense social, environmental, and economic benefits of upzoning means that Councils should still be financially rewarded for meeting their targets.

Sticks

Councils that fail to meet their targets three years in a row and cannot demonstrate they have made a genuine attempt to course correct should be penalised.

This penalty could take several forms. We outline three basic incentives below:

- Councils that fail to meet their targets should be required to pay an annual ‘Housing Remedy’ to the state government. The proceeds of this should be hypothecated toward Homes Victoria. To increase political salience of the ‘Housing Remedy’, we suggest it take the form of a line-item added to every ratepayer’s annual bill.

- Councils that fail to meet their targets should be made ineligible for select tranches of state government infrastructure grants until they course-correct.

- Councils that fail to meet their targets should have councillor call-in powers suspended. All planning applications should then be delegated to council staff.

As part of these reforms, the government should explore reforming the current rate cap imposed upon Victorian Councils, ensuring that the Housing Remedy can be enforced without impacting any essential services.

Failing targets

In the case that a council believes its target was not met due to other factors beyond its control, they should be able to appeal the penalty to an independent committee.

Due to low demand

Because demand is directly factored into our housing targets model, a council will never be penalised for lack of housing demand in its area. As demand lowers, so will prices, and so will the housing target.

To account for any lag in the model, we recommend annual updates, and that councils only be penalised if they fail to meet their target for three years in a row.

Due to sector-wide challenges

If construction or other sector-wide challenges prevent most council areas from meeting their target, then the State and Commonwealth must act immediately to increase capacity in the construction sector. Councils should not be penalised while this capacity is being created.

Due to existing development controls and overlays

Existing heritage, neighbourhood character, and design and development overlays in place over large swathes of our inner-suburbs should not be an excuse for councils to miss their housing targets. Councils with far-reaching overlays will need to consider how best to achieve their housing targets against the tradeoffs associated with maintaining high opportunity-cost overlays.

If heritage is a barrier to growth within a given LGA, then that LGA has four options:

- Adjust heritage controls to allow more density on heritage and character land

- Remove controls from properties of low heritage or character value

- Increase zoned density further in non-heritage and character areas to allow adequate housing growth while maintaining heritage areas

- Be subject to the Housing Remedy until targets are met

Methodology

Calculating housing targets

Our model’s housing targets are calculated in seven stages, as follows:

- Sites that are parks, schools, hospitals, or already have apartments are excluded.

- Potential yield for MMZ lots is calculated. Any lot zoned “Missing Middle” is considered suitable for 6 storeys of housing with high lot coverage. The potential yield of these properties is calculated based on the yield achieved by 6 storey Nightingale developments in Melbourne.

- Potential yield for RGZ, GRZ, and NRZ lots is calculated. This is based on the density calculated by Professor Michael Buxton.

-

Costs are calculated. For each lot, the cost of

demolishing the existing home is calculated, plus the

cost of building 85 square-metre GFA apartments in its

place. Taller buildings are considered more expensive

to construct owing to increased structural

requirements. Because the Residential Growth Zone has

parking requirements, the cost of underground car

parking was added to construction costs for lots in

this zone. The full cost calculation formula is

available

here.

- The value of existing properties is calculated. This uses a regression of past house sale prices against features of the land such as the current zone, lot size, distance from CBD, SA3, and distance from public transport. The full regression terms are available here.

- The likely price of apartments sold in a development on a given lot is calculated. This uses a similar regression as above.

- Profitability is calculated. For each site, the profitability of a development was calculated at various heights within Missing Middle zoning. Each site where calculated profit is greater than 0 contributes to that LGA’s housing target.